If we all had access to a time machine it might be a good move to scoot back to the late 1960s and buy a twin-cylinder 500. Not to bring back to the here and now, that probably wouldn’t be allowed, but simply to love and to leave to ensure that there would be a lot more 500 twins for everybody to enjoy 50 years down the line – ready for when the pool of exotic bikes slipped forever beyond the reach of Mr Everyman and riders finally came to their senses and admitted that 650 parallel twins are truly hard work to live with.

It’s an interesting thought and certainly one shared by Jim Hastilow who does his classic biking on a budget, but still wants to ride something with a bit of style and performance that doesn’t relegate him to vintage vehicle parades and tootling around country lanes on sunny, Sunday afternoons. “Times have really changed. I once bought a BSA B31 for £150. I had a modern bike for daily transport so I guess the BSA was a hobby, pure and simple. I brought it home in two tea chests and took three years to piece it back together, not really knowing what it was until the Owners’ Club confirmed it was a very early postwar model that left the factory in 1946.

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

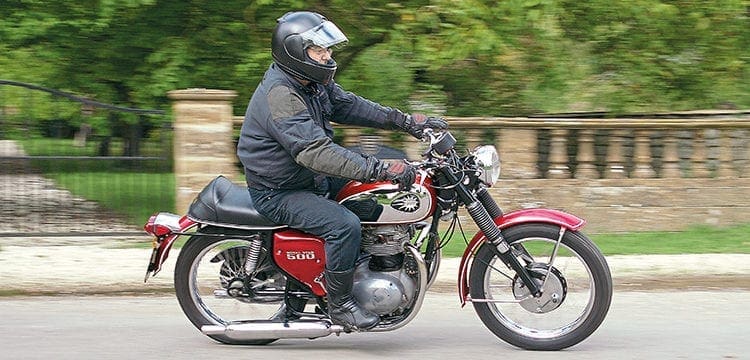

A chap from Holland contacted me – he had factory records that showed the bike had been dispatched to BSA dealers Millards in Guernsey, who, I believe, are still going. How it wound up back in the UK is anybody’s guess but it was great fun to ride – a real survivor.” “Nowadays, finding bikes for restoration is difficult because there is so much interest, both from dealers who sell ‘barn finds’ for thousands of pounds, to a world-wide market on the internet, and from people who can afford to throw money at a nut and bolt restoration irrespective of the condition of the bike they have. Cost has outstripped actual value; unfortunately that’s the way it is, but it has narrowed the field a great deal.” Two years ago, Jim was running a Triumph Daytona, a peppy twin carb machine with high compression pistons and a growing reluctance to start. He had, he freely admits, become disenchanted with the brand and swung his allegiance to the stacked rifles of Armoury Road, Birmingham. Or at least he began to seriously consider a BSA as a viable replacement for the Daytona. “BSA twins from the late Sixties are extremely solid-looking, and the motors of the 500s are, if anything, over-engineered. Overall, there’s less fuss about a BSA.”

All true, but not quite the tone of the company’s advertising which was focussed on the high performing 650 Thunderbolts and Lightnings. Then again, perhaps it was the tone of the advertising that had a lot to answer for – the A50 Royal Star was billed as ‘smooth, quiet, dependable – your best choice may be a Royal Star’. All a bit low-key at a time when the motorcycle world was teetering on the brink of the Superbike era… Not surprisingly, the 500 twins didn’t sell in great numbers and by 1968 there was only one model left in the BSA catalogue. So how did Jim go about finding his Royal Star? To start with, he set himself a budget, £2,000, to cover the initial purchase. He knew he was unlikely to find anything remotely spectacular at such a modest price, possibly half the going rate for a bike on the road, but it put his quest into perspective. Jim was well aware that any bike in that price category would require work. Another project in fact; although hopefully not one that came in tea chests this time. And although he felt confident to tackle the bulk of any restoration himself, there would inevitably be a long list of parts that needed replacing, as with any bike that was going to be roadworthy, let alone a reliable runner – a hidden expense that is so easy to overlook at the initial purchase stage.

Autojumbles regularly turn up bikes of the less sought-after category and it was at the VMCC Shepton Mallet jumble that Jim found his BSA. He describes it as “essentially a collection of parts in a frame and everything very rusty”, although by autojumble standards it wasn’t that shabby. Looking at a photograph of the machine in ‘as found’ condition, it looks pretty complete and all the parts – petrol tank, seat, side panels, mudguards and wheels – look to be the right ones. How often have you seen a bike that has been thrown together with all manner of bits and pieces being passed-off as original! True, the A50 had spent a fair bit of time in the damp and there were obvious things missing like the primary chaincase cover and the clutch cable, but the engine kicked over and the wheels turned, so it was well worth considering. A possible bonus was that the engine was supposed to have been rebuilt by the last owner, which may or may not have been true of course. And if it was true, how good a job had he made of it? A better bonus was that after Jim had decided to buy the bike, another guy who had shown an interest in it turned out to be a bit of a BSA fanatic and offered him a primary cover and a good condition, original headlamp shell to get the restoration under way.

Back home, Jim cleared a space in his workshop and began the careful process of dismantling the bike, photographing every stage of the procedure with his trusty phone. It came apart extremely easily, leading him to believe that it had been stripped for a rebuild in the dim and distant past (it was last registered in 1982) and then loosely reassembled to sell at the autojumble. That would explain why the exhaust system was in such good condition, bright chrome on the outside and soot free on the inside – it had been bought brand-new all those years ago and never fitted. Corrosion was evident all over the chassis; it had wrecked the wheel rims and gnawed deep into the metal of the petrol tank. Jim was doubtful that the tank could be salvaged and, even if it could, it would never match the quality of the original so it had to be scrapped. Both glass fibre side panels were badly cracked around the mounting holes, the seat base was rusted and the cover torn. Parts were coming off and, wherever possible, earmarked for repair, but in the case of the tank and wheel rims, new or good condition second-hand replacements would have to be found.

The condition of the engine was still unknown so Jim broke out his trusty endoscope to have a look around inside. The endoscope, a mini camera and light attached to the tip of a flexible wand connected to a hand-held screen, has been applied in medical scenarios for ages (please feel free to shudder) but it is a relatively new toy in the DIY mechanics toolbox. Having said that, there is now a wide choice available and use of the industrial models isn’t restricted to poking around inside tanks, cylinder heads and crankcases. “If you can hear something running and it doesn’t sound right, it smokes or it leaks oil, you know you have some work to do. But there’s no point in taking something apart unnecessarily,” is Jim’s approach. He couldn’t find a trace of dirty oil inside the crankcases and the tops of the pistons looked brand-new. A leak-down test, another motor-trade practice that can be undertaken at home with an inexpensive set of gauges and a source of compressed air, indicated a 15% drop on both cylinders which confirmed that the engine was in fine condition.

“I had been worried when I took the carburettor off and couldn’t make any sense of the jetting,” says Jim. I spoke to Amal specialists Burlen Ltd in Salisbury and they told me the carb was set up for a two-stroke, the body size was right for the A50 but the internals were not. Something like that can be quite disconcerting but then I reminded myself that the bike had been assembled to sell, not to ride away. And there was no problem getting the right jets, slide and needle.”

Read the full story in the August issue of CBG!

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

Advert

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.