Photos: Simon Everett

Not all specials are Tritons, and not all Tritons are special. BSA also built some great, strong frames, and some riders fitted them with Triumph engines. Here’s one now…

It’s funny how history rewrites itself. Or gets rewritten by others, of course, until The Way It Was becomes muddled into several lesser versions, such as The Way We Wish It Was, or maybe The Way We Want To Remember It.

And few areas of human self-indulgence reflect this better than the nostalgia business, where the lenses are either opaque or rose-tinted – or both – and where the past is strangely moveable.

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Everyone is an expert on Tritons. Everyone over the age of 50 certainly owned one and probably built several themselves, using genuine Manx frames and pukka race-tuned T120 motors. Didn’t we?And we all revere the Triton because of its glorious competition heritage – right?

The slightly less glam reality is that back then, when none of us knew better, we all believed the Triton hype – and there is nothing wrong with that, nothing at all.

Building specials is fun, and if the riding of the result was too often more comedy than competition… well, that’s youth, hey!

The creative nostalgia boom has ensured that not only have a truly remarkable number of Tritons survived from the 1960s and 1970s, but that folk are still creating them today… a minor mystery in itself.

Where have all the TriBSAs gone?

Thrashed to death, every one of them, probably, given that in at least one reality – my own – a lot more TriBSAs were built than Tritons, and the majority of them were genuine destruction derby competition warriors.

Tritons starred in the cult of the café racer because that was what they were, café tackle. TriBSAs, though, were something else.

In the same way that the ‘ultimate’ Triton was that Manx/Bonneville mixture, so the ‘ultimate’ TriBSA was the same T120R engine in a Gold Star bicycle, track tearaways every one. Except, that like the Tritons over in the café corner, the TriBSA was very often a little diluted on the genetic front.

Think about a nice all-iron Triumph 5T engine, driving through a BSA gearbox to a back wheel mounted in a B31 frame.

It was possible to build a bike like that – a marriage of trashed Triumph and powerless plodder – for very little money, back in those days of breakers’ yards rammed with the things.

And, oddly enough, a lot of riders did. Not necessarily the café cruisers, but also the mud-masters who spent their weekends hooning around any road without a tarmac topping, having a great time at very little cost. Except possibly to their physical wellbeing, of course.

It’s not easy in these modern times to explain that Norton featherbed frames were never cheap. Unless they were bent… in either sense of the word.

Although Nortons equipped their pleasant but plodding singles with featherbeds, and indeed the 350cc Model 50 was probably the major source of frames for roadgoing Tritons, BSA built an awful lot more of their own deliberately pedestrian non-sporting singles than Norton built bikes in total.

So Norton frames were rare and expensive, while BSA frames were the opposite. And, of course, in the same way that every featherbed started life as a works Manx racer, so every BSA duplex frame started out wrapped around a DBD34 Gold Star engine.

Proud owners could point to the characteristic kink in the lower right-hand frame rail and share the assurance that ‘only Goldies have that’. Which is nearly true, and all swinging arm Goldies did indeed share that historically hammered frame tube.

However, not all those bashed pipes were battered to clear Goldie crankcases: they were beaten into surrounding the oil pump… of all the singles. All of them, not just Gold Stars. BSA built an awful lot more B31s than DBD34s. That, gentle reader, is a fact.

And the reason for this slightly lengthy preamble is because the bike you can gaze upon in silent awe in Simon Everett’s delicious photos was built around the frame from a genuine, historically exact… B31. That is correct.

The beast before you started out in 1954 as a device intended to cart dad to work every day. It would have boasted huge mudguards, probably an entirely enclosed rear chain and would have been finished either in funereal black, nauseous green or a peculiar shade of reddish that defies sensible description.

And the owner of this TriBSA at the time of our test, a fine fellow called Chris, was entirely happy to reveal its ancestry. And why not?

The basic B31 frame is every bit as robust and dynamic as tubery from a DBD34 GS. And this bike was built to be dynamic. Exceptionally dynamic. There was neither need nor wish to pretend that it was something it’s not.

Likewise with the engine. There’s nothing special in its history, but there’s an awful lot that is special about it now, like the Morgo 750 conversion, to which we will return shortly.

As is the case with the BSA swinging arm frame, so it was with Triumph engines. Almost all of them in a given year used the same basic castings.

Once the unit construction era appeared, the 350 and 500 twins used entirely different castings to those of the 650s; prior to that the 500 and 650s used the same crankcase sets. Those on this engine started life as a 5T, a Speed Twin.

I don’t know the year, but the model’s designation is stamped in the cases, unbodged in any way, as is not always the case with specials. So, returning to an earlier remark, it is entirely possible that at some point in its history, this astonishing machine started out when a crashed Speed Twin donated its engine to revive a terminally weary B31.

Not that the 5T Speed Twin was a rocket, but it would have been a lot more exciting than a B31.

And that, I’m afraid, is that for the history bit. There’s no outstanding provenance here, no glorious racing history, no TT adventures with noted names gripping the tank with their knees as they thrashed the might of Japan… none of that.

Oddly enough, back in those misty and faraway days, I knew several riders who built TriBSAs for scrambling, both solo and sidecar, and almost all of them started out as iron 500 twin engines in B31 frames. We can only wonder whether this one did… if so it’s come a long way since then.

Right, the engine. It may have started out as a cooking all-iron 500, but it’s come a long way since those days.

Nowadays, this is a 750, alloy top end beast of a thing which uses those old crankcases – which is perfectly OK from an engineering perspective, as they’re the same cases as used in the T110 or early T120.

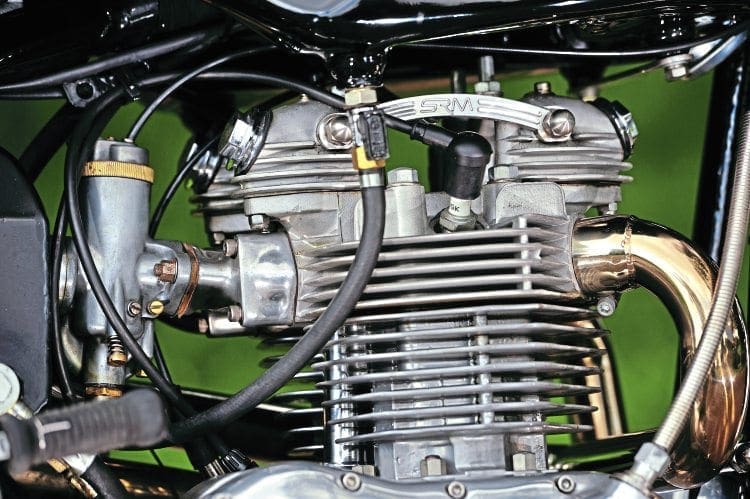

They have the larger main bearings and if you don’t know how to tell this, there should be a pic with a helpful caption hereabouts, and as the top end is by Morgo (subtle, huh?) there may be a Morgo oil pump buried inside too.

It’s not easy to persuade an owner – even a very generous owner – to strip an engine so you can check out the oil pump. I know we should, but asking is a chore and refusal often offends. Morgo oil pump?

A conversion which supplies oil to the engine through a gear-type pump rather than the original plunger variety. The idea being a continuous feed rather than a series of pulses.

The Morgo kit itself comes with a new barrel, rather than relying on over-boring or re-sleeving an original, and when the barrel was designed, the cooling fin area was increased and their pattern altered to add strength. And to look good too.

You will have observed by now that the engine breathes through just a single carb, and that’s an Amal Monobloc, rather than a pair of Concentrics, which is what we’d expected to find.

Nothing wrong with a Monobloc in decent condition, which this is, and if outright power is not the objective, it makes a lot of sense to stick with a single instrument rather than a pair.

The allegedly leak-prone rocker oil feed has been replaced by an SRM alloy item, which is a thing of wonder, and the engine is in fact commendably oil-tight and mechanically on the quiet side.

That brings us neatly around to the exhaust, which is also a thing of wonder, being of a design rarely seen on older, allegedly classic bikes. We can’t find out who made it, but can confirm that it’s stainless, with a neat alloy end can, and was intended for the track, as we say.

The considerable noise is apparently inoffensive. To the deaf, most likely, although it may also be music to others’ ears. These things are relative and subjective too. Power from the engine runs through a belt to an NEB six-plate racing cutch.

Let’s go racer!

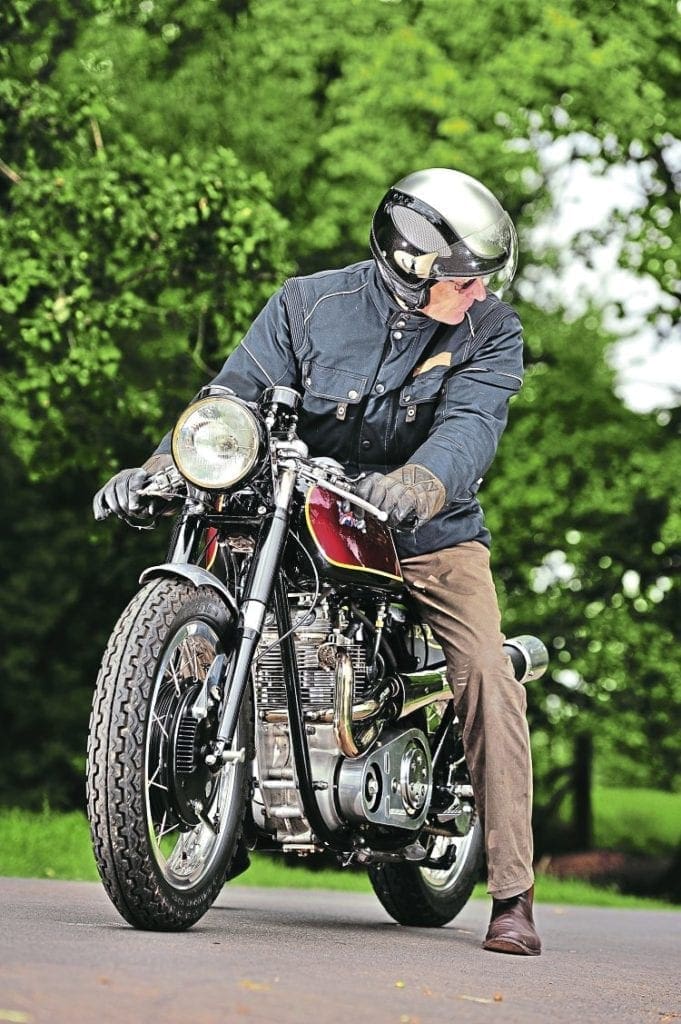

It’s not easy to tuck away a rider who’s well over six feet tall, but perseverance is its own reward, as they say

As you can possibly observe from the absence of a primary chaincase, the primary drive runs entirely dry, and as a consequence of this the clutch action is… shall we say… a little sudden, and it emits something of a protesting screech when the power’s fed in sharpish, as when making a swift getaway from a standstill.

This all adds to the sturm und drang of the riding experience, which translates literally as ‘storm and urge’, and that sums up the whole thing pretty well. The gearbox is a BSA unit, nothing noticeably flash about it, and it shifts cleanly and accurately.

According to the stamping on the outside of its casing, this is a standard box with a standard set of ratios, rather than the RRT2 type commonly found on rapid (BSA) rockets, Gold Stars and the like, and is all the better for it on a road bike.

Using a BSA box in a special, like using a Norton box in a Triton, allows the chainlines to work together as the frame designer intended, and although the join between crankcase and primary cover is hardly visually elegant, the power train works together very well indeed.

The BSA frame appears essentially stock, along with the front forks, although these use a Taylor Dow ‘Superleggera’ alloy top yoke, as was traditional when fitting clip-ons, back then.

Where the front end is radically different from BSA-based specials is in its use of a seriously serious front brake.

This, a 4ls brute from Grimeca, is one ace bit of kit, with a light progressive action and considerable sensitivity, as well as track-standard decelerative ability.

The brake is much better than the fork, to be honest. Rear anchorage is less impressive, being a BSA/Triumph conical hub modified to resemble a Manx device – though there’s nothing wrong with that – and using the original sls mechanism. Works well, enough, too.

Serious stopping stuff alert. Twin sided brake with a pair of leading shoes on each side makes for considerably competent anchorage.

Atop all this sits a Lyta fuel tank, a neat racing seat, below which is a really unusual piece of BSA history – an oil tank from a Catalina Gold Star. Neat. That’s the word for this bike – neat. But any motorcycle is only as good as the riding experience. And this is great.

It’s not especially fast, although it feels it… and it certainly sounds it.

It’s not smooth, it’s not sophisticated, but it feels fast – maybe as fast as a BSA Rocket Gold Star, which in fact it resembles as a riding machine, with that level of non-compromise, that level of dedication.

Kicking up requires a certain determination, although the bike’s decently low-slung, so getting the knee and ankle to do their collective stuff isn’t a stretch. The compression is high and the capacity large, though, and first gear feels pretty tall, making that kicker’s determination a good thing if kickback is to be avoided.

Ignition is by magneto, ye goode olde Lucas K2F, badged in red as a ‘competition magneto’, which may well be the case, although it’s not easy to tell without a level of magneto expertise, which is sadly lacking hereabouts.

The single greatest advantage of a magneto is that it requires no other electrical wossname to assist in its spark delivery function.

This is just as well, as a careful study of the bike (or indeed of the pics) will reveal no charging device for the battery, although lights are present, correct and functional enough for an MoT.

As this machine is – obviously enough – not an iconic Triton, and therefore need not follow established iconic Triton style statements, it’s allowed to sport a seriously… ah… sporting exhaust, which it does. It’s loud.

It’s not offensive. Mostly.

A gentle hand on the throttle would be polite on a suburban racetrack, unless you’re feeling particularly antsy, in which case you have a perfect audible means of approach, and indeed of departure, for standing behind the TriBSA is an impressive experience.

We’ve no idea who actually fabricated the system, but it sounds remarkable, looks remarkable and appears to flow gas remarkably well, so no complaints here.

In the classic café world, the featherbed is the frame against which all others are measured.

As discussed above, the BSA frame is perfectly fine, and this one handled the grunt from the 750 Triumph engine with no obvious signs of distress.

It’s helped in this task by a set of anonymous (but handsomely yellow) rear shocks, which work very well in both springing and damping departments, and by stock-looking BSA forks up front.

The brakes are excellent, as you’d expect, and although by its very definition the TriBSA is a special, it rides like a machine whose components were intended to work together.

Because they do… work together, that is. It’s easy to get into the riding rhythm. You get all the shake, rattle and roll of a real rocker’s bike, and when you park up and slide from the suede-upholstered seat to do the obligatory posing and admiration things, the TriBSA delivers.

Everyone stares. Not everyone on other two-wheelers can work out what it is, because it’s not an iconic Triton of course, but they all recognise instantly that it’s a special, which is what’s probably important to most riders of machines like this one.

So, given that even very dodgy Tritons appear to command impressively high prices in these strange days, can an allegedly lesser special, based around a BSA instead of a Norton, deliver the classic café experience? Of course it can.

We’d go further; several of us in and around CBG prefer the riding experience of the BSA bicycle to that of Norton’s featherbed.

Sacrilege of course, but also true. Try it for yourself, maybe? And if you’re bent on building a special special of your own, consider the humble BSA as a basis. You might get a pleasant surprise…

Read more in the December 2019 issue of Classic Bike Guide – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.