When two young friends approached Edward Turner and suggested supercharging a Speed Twin to break the Brooklands lap record, they were dismissed with a wave of the hand. But they did it…

Words: Phillip Tooth photography: Phillip Tooth and Wicksteed archive

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

When Ivan Wicksteed and Marius Winslow were packed off to Bedales, a private boarding school near Petersfield, their parents had no idea that they would become great friends and go on to build the supercharged Triumph that would break the Brooklands 500cc lap record. But this was a school that nurtured individuality and initiative, and as far as these boys were concerned, that meant riding and tuning motorcycles.

Back in 1932 Ivan borrowed a 250cc BSA and won a bronze medal in the Schoolboys’ Trial. A year later he was riding a 500 Norton, which propelled him to a silver medal, and then in 1934 the friends bought a 350cc Cotton-Blackburne. Marius wielded the spanners and the bike was prepared for their first race at Brooklands on July 28. With the Webb forks legs taped up to reduce drag and the fishtail of the Brooklands can extending 10in behind the rear mudguard, Ivan covered the flying kilometre with a speed of 76.61mph and that was it – they were hooked on speed.

The Cotton soon made way for a four-valve, twin carb 250cc Excelsior Mechanical Marvel and they started winning races. By this time, Ivan was an engineering student at Loughborough College – he said that he only enrolled so that he could learn welding. Money was tight and, when Marius suggested he move to London where they could start their own motorcycle tuning business, Ivan replied that he couldn’t afford the rent. Fortunately for the friends, Marius had wealthy parents who were bankrolling his adventures and he said he would pay Ivan a salary. Ivan wasn’t exactly a ‘works rider’, but it was a start.

And soon they were really motoring. In May 1936, Marius tuned a 500cc Rudge-JAP and Ivan won a Gold Star and a pair of Meyrowitz goggles by lapping Brooklands at over 100mph, winning his race by 100 yards. Then he borrowed Jock West’s old 494cc Triumph single and won the last race of the season with three terrific laps, one at 110.68mph. Ivan was 19 years old.

The Brooklands Gold Star wasn’t made of gold and it wasn’t very big – it measures just 13mm across the points – but it became one of the most coveted awards in British racing history. Introduced in 1922 by the British Motor Cycle Racing Club, it was awarded to anyone who lapped the track at over 100mph in a race. Only 125 would be awarded before the track was closed when Hitler started messing things up for everyone in 1939. There was also the ‘Double Gold Star’, awarded for lapping in a race at over 120mph. Only two riders had achieved this feat – Eric Fernihough and Noel Pope, both riding supercharged 1000cc Brough Superiors.

That must have got the pals thinking. If they could Double Gold Star on a 500 it would really put Winslow and Wicksteed on the map and there would be queues of riders outside their workshop, desperate for them to breathe more life into their bikes.

Superchargers work fine on multi-cylinder engines, because when one inlet valve is closed, another one would always be open. But supercharging a single isn’t easy because the pressure would build up when the inlet valve was closed and there was nowhere for the blown gasses to go. The answer was to use a large plenum chamber to store the pumped air until the valve opened again.

Aussie Phil Irving tried supercharging a 500cc Vincent-HRD for the 1936 Isle of Man TT. It certainly attracted a lot of attention but lap times don’t lie and the blown bike lapped 21sec slower than a standard Vincent.

When, in July 1937, Triumph revealed advance details of their new 5T vertical twin, the pals realised that there was the answer. As Edward Turner, chief designer and general manager, pointed out, the firing intervals were even – one piston was at top dead centre (TDC) on the compression stroke, while the other was at TDC on the exhaust stroke – and so there was an even pull on the carburettor. The vertical twin also offered ‘extreme rigidity’ and perfect cooling (even better than a single) and would fit into a smaller frame than a V-twin. Unlike on a classic V-twin, the two cylinders did exactly the same amount of work and what’s more, his engine was amenable to all single-cylinder tuning techniques.

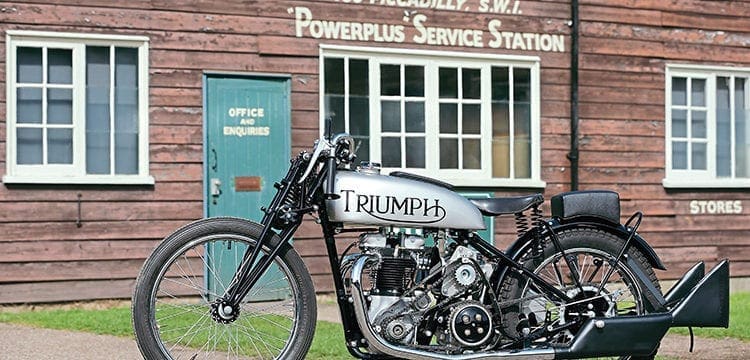

The Triumph Speed Twin would form the basis of the bike that would break the Brooklands 500cc lap record and we know exactly how the pals did it, because Ivan kept a scrapbook filled with photos, press cuttings and notes, while Marius wrote down every minor modification, every failure and every success in his workshop diary. And Ivan’s son Michael has given us access to both.

“I feel sure that our only reason for ever getting the lap record was the very cold reception we received from Mr Edward Turner, when, at the London Show in 1937, two rather young and innocent chaps walked up to a smart salesman on the Triumph stand and asked if they could see Mr Turner, and much to their mutual embarrassment they were told they were doing so,” wrote Ivan. “After that, the conversation went something like this. ‘Oh, we are sorry, but we wanted to say that we are very keen to blow one of your motorcycles as we feel the design lends itself almost ideally, and we would like your opinion on the idea’.” That didn’t impress Turner, who dismissed them with a wave of the hand, as Ivan recalled. “This was answered by the following retort. ‘A very logical conclusion. Good afternoon, gentlemen!’”

With no prospect of a discount from Turner, the pals turned to Ron Harris, a Brooklands racer, who had a motorcycle shop only 20 miles from the speed bowl on King Street, Maidenhead. Marius ordered a Speed Twin with less lighting and silencers but with sports mudguards and a large oil tank.

On the first page of the notebook that covers the period between January 19 and November 23, 1938, Winslow writes: “Triumph Model 5T General Information. Frame No. TH.3477. Engine No. 8-5T 9135.” He measured the bore and stroke, confirming both pots were 63 x 80mm, checked the valve timing and magneto advance (30˚), the valve lift (5⁄16in for all four) and valve head diameter (15⁄16in inlet and exhaust), and the compression ratio (6.95:1). Then he noted the volume of the combustion chambers (42cc), the dimensions of the exhaust pipes (50in long, 15⁄8in bore) and the valve spring pressure on the seat (85 lbs) and at full lift (145lbs).

After dismantling the engine, Marius writes on page two: “The valve timing and type of cam are anything but what might be desired, but this will have to be made the best of.” The neat, small handwriting tells you everything you need to know about Marius Winslow and his attention to detail.

He wasn’t impressed with the crankcase castings. “They are not a very good job,” he noted two days later, before cleaning them up by filing off the casting marks. A hole was bored in the timing chest cover so that he could use an extractor on the magneto pinion without removing it. The centre flywheel was polished with emery paper and the crankshaft trued up to 0.0015in at both timing and drive sides. “At first it was much worse than this.”

The big end shells were hand-scraped to a nice easy fit and the crankshaft was carefully balanced to 45% of reciprocating weight. Then he got to work with a rotary file, opening up the inlet ports from 7⁄8in to 15⁄16in so that he could use a pair of Amal racing carburettors, but he damaged one of the valve seats and had to order a new head.

“Mr Turner, in his efforts to keep weight down, had not obliged us by leaving plenty of metal around the inlet ports, and we began to wonder whether our task was too great,” wrote Ivan. Marius made bronze valve guides for KE965 austenitic steel valves, with 1⁄4in stems (standard 5⁄16in) and larger heads, but he screwed up cutting the valve seats because the valve guide holes were not bored to the right angle. “This is the second head to go on the scrapheap! Hey ho!”

Head No.3 was ordered and this time Marius was more careful. He cleaned up the valve rockers, reducing the weight by six to eight drams (that’s about 10-14 grams). Grinding down the end caps of the steel pushrods saved another dram per rod. He also fitted Martlet pistons that gave a compression ratio of 10.074:1 (how precise is that?) and reduced the combustion chamber volume to 25.5cc. By moving the inlet cam pinion one tooth the valve timing was advanced to open 45° before TDC (the standard is 25), while moving the exhaust cam pinion retarded the closing by 5°.

On Friday, February 18, Marius installed the engine in the frame and joined up the petrol and oil pipes. The steering damper was modified with a 7⁄16in Whitworth thread instead of stock to make the action quicker, and one week later the pals filled the tank with Pratts Racing Ethyl and they were ready for the first test at Brooklands. It didn’t go well. “Start on 831 plugs. Oil not returning. Take off timing chest cover and take down oil pump. Get this OK. Delivery then packs up. Find a bit of brass under ball valve on delivery side. Get this OK. Go out on track. Partial seizure. Petrol tank leaking like hell!”

After the engine had been stripped and the pistons eased, larger main jets were fitted and 2% castor oil added to the petrol. They were back at Brooklands on March 2 when Ivan covered 24 laps, with a speed of 100.61mph on the second. “Question: Why a 1150 jet on a 250 with a 10:1 compression?” Marius asked himself. But the frequent visits to the track were paying off, and on Saturday, March 12, Ivan finished fourth after starting 12sec behind the first man away in a handicap race, with a best lap at over 107mph. Two days later, Marius wrote: “Interviewed Grenfell re supercharging the job.” Granville Grenfell had tuned a Duplex-steering OEC-JAP with a supercharged 1000cc V-twin, so he might have a few ideas. “Decide to use one Arnott Concentric supercharger size 102 and Amal carburettor. However, he is a bit loopy and will very likely decide to change all this.” Ivan added: “We had no scruples about picking everyone’s brains – the Bickells, Baragwanath, Fernihough, Grenfell, Beart, the Jacksons and the Archers.” It was a list of Brooklands greats. “But there was surprisingly little consistency on any one point and we had to finally make our own decisions.”

At the end of the first week working on the supercharged Triumph, the saddle tube had been cut just above the gearbox draw bolt lug and below the top chain stay lug. Two double-lugs were fabricated and brazed into the each end of the saddle tube. Mild steel plates 3⁄8in thick were bolted to the lugs to support the supercharger. Two sprockets were brazed on the splined shaft of a JAP sprocket carrier. The inner sprocket carried the primary chain, the outer one the drive to the blower, which ran at ¾ engine speed. A tensioner was fitted to the blower drive chain to take up the slack. “The blower is much overhung to the driving side of the machine to line up with the sprocket,” noted Marius. The bike was built up with a 19in front wheel to lower it a bit (standard was 20in). “My part of the job is about finished,” he wrote on April 2, “the outstanding things being to get Anstead to make the oil tank, and Grenfell to do the plumbing.”

Read the full story in the December issue of Classic Bike Guide

Advert

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.